Afghanistan’s currency crisis leaves millions at risk of starvation

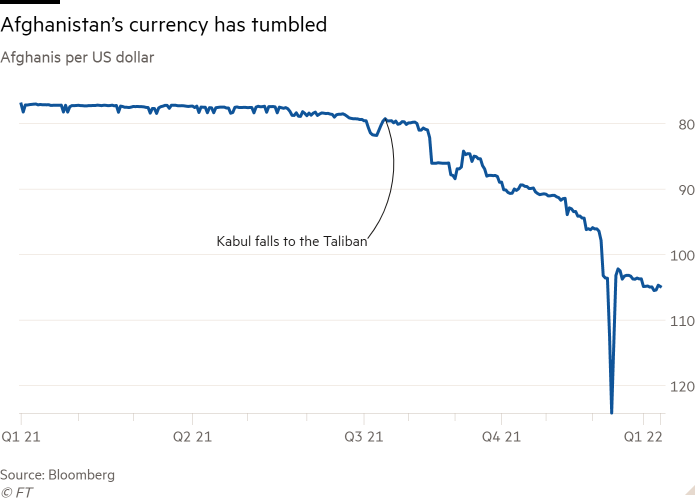

Afghanistan’s currency has plummeted about a quarter since the Taliban seized power, exacerbating an economic crisis that has left millions of people in the import-dependent country facing starvation.

The afghani has fallen to 105 per dollar from about 80 before the hardline Islamist group’s August victory, making it among the world’s worst-performing currencies over the past six months. It is second only to Turkey, where the lira has been battered by Recep Erdogan’s unorthodox economic policies.

In Afghanistan, withdrawing US and allied powers cut off the funding that made up 80 per cent of the government’s budget, froze more than $9bn in central bank reserves and enforced sanctions that have paralysed the financial system. Banks have been unable to operate properly and public workers such as doctors and teachers have not been paid.

The afghani’s weakening has stoked what international aid agencies consider the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, pushing prices for essential goods beyond the means of desperate Afghans. More than half the population is facing food insecurity, a disaster exacerbated by the freezing winter.

Mohammad Farid, a curly-haired fruit seller in Kabul, makes so few sales that his modest business is running at a loss. His colourful display of golden and red apples is slowly wasting, having sat mostly unsold for four days.

“Afghanistan is a mess,” he said, adding that he would have been happy about the end of the conflict were it not for the economic meltdown. “I wanted it in a different way — where there would be work, business and income.”

During 20 years of US and Nato occupation from 2001, Afghanistan’s economy became dependent on foreign aid and the dollar. Greenbacks were flown into the country and Da Afghanistan Bank, the central bank, conducted regular auctions to support the afghani.

The sanctions mean that Afghans, businesses and public institutions are cut off from savings, overseas customers and international donors, worsening what the IMF expects to be a 30 per cent economic contraction.

The UN and US last month announced exemptions to allow humanitarian aid into the country. But critics maintain that sanctions are punishing ordinary Afghans rather than the Taliban.

It is the “economic chokehold imposed by the west that creates a need for humanitarian aid”, argued Graeme Smith, a senior consultant at the International Crisis Group, a think-tank. “Having a central bank is an essential service for a modern state economy. The easiest thing would be just to allow the DAB to do their work.”

Shah Mehrabi, a professor of economics at Montgomery College in Maryland, who sits on the board of the DAB, said the US should allow transfers of about $150m a month to allow the central bank to resume currency auctions and stabilise prices. “Why not just allow this process to establish some degree of trust [in the] DAB, which is an institution we invested 20 years in? Why go ahead and dismantle this institution?” he said.

Currency traders are ubiquitous in Kabul, lingering near traffic lights or packed into bazaars. Several said dollars were being smuggled out of the country to Pakistan, which has also been hit by a sharp currency depreciation.

“When Pakistani tycoons see their currency is coming down, they try to buy dollars,” Mohammad Mirzai, a 22-year-old trader, said. “In Afghanistan, there are no rules. They’re buying from Afghanistan and trafficking dollars into Pakistan.”

Analysts said that the afghani might have deteriorated further given the magnitude of the crisis, but the difficulty accessing savings has strengthened demand for cash.

Charlie Robertson, London-based economist at Renaissance Capital, an investment bank, said in other instances of economic collapse — such as in former Soviet states or Zimbabwe — central banks resorted to printing money to pay their bills.

But the DAB depended on foreign companies to print bills and lacked the facilities to do so itself. “For a country in Afghanistan’s situation it’s actually surprising the decline has been so small,” Robertson said.

While the relatively limited currency collapse has helped prevent hyperinflation, price rises are still making vital foodstuffs unaffordable, increasing the threat of widespread hunger.

Hamidullah Ibrahim, a 61-year-old currency trader, bemoaned that prices of flour and oil had all risen sharply. “Everything,” he said, “has gone backwards.”

Additional reporting by Fazelminallah Qazizai in Kabul

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Education News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.